TBA:25 Dailies / Freddie Robins

Apotropaic at the Douglas F. Cooley Memorial Art Gallery, Reed College

[ All photos in this post, Ryan-Ashley A. Maloney ]

There’s nothing like looking at art your partner would love to soften the edges of a disagreement and diminish the importance of reaching a clear resolution—a resolution which, in my case, would include my husband telling me that I was right.

I don’t even remember what the disagreement was about.

But it was Sunday, September 14th and TBA:25 had, effectively, come to an end. I planned to visit the Cooley in the afternoon, after resting. If I could get enough rest. While I wouldn’t change anything about how many performances I attended during the festival, the crash that follows so much social stimulation is inevitable, and I mostly wanted to stay in bed.

But then the disagreement I can’t remember took place in the afternoon and the only thing I could think to do that might break my looping thoughts was to take my pickup for a drive (it was sunny) and play music too loudly with the windows down. I’m not the sort of person to just drive to drive, though—too wasteful for my constitution—so I drove to Reed.

In the same way that I’ve never looked up a person before an interview or first date, I also don’t research artists I’m unfamiliar with before going to see their work for the first time. It’s rare these days, with search engines and social media, to have a pure experience of anything and I relish the opportunity. So, when I walked into the Cooley to see Robins’ work for the first time, I had no idea where the artist lived, how old they might be, what gender they identified as, or what they did for work (if something other than art).

I was immediately struck by three things: how clearly the work communicated a sense of joy and unselfconscious curiosity; how much conversation there was between made and found objects (including salvaged items like cardboard boxes); and the uncanny way that the parts of the show felt both old and new, expert and naive, devised and improvised—contradictions that I believe are most often found in people with the confidence either of youth or experience, not so much in the in-between.

I noticed the rocks and shells stitched into rows of garter and imagined my own rock collection, my own pile of knitting, my colander filled with freshly rinsed seashells; saw the ways the cardboard was being used, and thought of the boxes I’d been planning to make but hadn’t started yet, for fear they might not be perfect enough (why should they be perfect, I wondered?); and admired the use of ‘office objects’—I love a steel binder clip and collect them myself, along with vintage clothespins, fountain pens, and pencil sharpeners among other things.

I still didn’t know where the artist lived, how old they might be, what gender they identified as, or what they did for work (if something other than art). I wished my partner was there with me because he would love this. Bennie and Clementine, whom I’d never met before, told me about the upcoming talk, the knit-in, offered me some exhibition catalogues, and asked me about my work—who I am, what I’m interested in, how I heard about the show.It’s not often I have such a warm, human-feeling experience at an exhibition space or art event.

Isn’t that odd? Why so much gatekeeping so much of the time around things that are made for everyone, intended so often to foster or communicate connection? Territorialism over access to something public—the making of something public, private—is confounding.

The weather was dreary the night of the artist talk a couple weeks later and, as somebody who is always looking for reasons not to leave the house, it took everything I had to muster the enthusiasm to venture out. Although I love artist’s talks, I almost always regret attending because nine out of ten times, the proceeding Q&A sessions are unbearable—so many people raising their hands not to ask generous and generative questions that allow everybody in the room to learn something more about the artist and their practice, but rather to go on about themselves—leaving me feeling torn between leaving during the Q&A (which always feels a bit rude) and sitting through it despite mounting anger.

Dialectical Behavior Therapy is teaching me about half smiles (which give me the look of a milk-drowsy toddler but actually did help me feel calmer during the germination of a road rage incident yesterday) and open hands, so I’m going to try to use that technique next time I feel my blood pressure rising during narcissistic audience member monologues.

Spoiler—the Q&A following Robins’ talk was spectacular. But we’re not there yet.

My husband and I decide to brave the mildly uncomfortable weather to go hear the talk.

We walk into Eliot Hall, a gorgeous chapel neither of us have been to before, and scan the room to see if we can figure out which person is Freddie. We can’t. What we notice, though, is that the room is absolutely packed. It’s humming warmly and there are several faces I know. There’s emotion in the room. The anticipation of grief. The air pregnant with goodbye.

I don’t know if what I’m feeling is inside of or outside of me, if I’m experiencing sensitive awareness or personal reflection pricked by the meditative murmuring all around.

Stephanie Snyder, the curator of this show and also the Cooley Director, begins thanking people—long-time colleagues, peers, and friends—for all the ways they have supported her along this journey, a portion of which, apparently, ends tonight.

She says something like, “This will be the last one these talks that I give here.”

I feel a rare moment of belonging. Collective grief. Grief. A familiar feeling. A thing I know what to do with. I’m transported to my single digit years in rural North Carolina.

My mother believed it made her look like a good mother to take me to church once in a while, but she didn’t enjoy it and never wanted to go somewhere she’d be recognized. So she’d pick a church at random one miserable Sunday a month, we’d get dressed up she and I, and we’d go. Always a guest, never a member.

I hated these Sundays, which marked the imposition of scratchy tights and my loathsome special occasion patent-leather Mary Janes, and I’d kick and scream the whole way. Then, once we were there and settled, the pastor or preacher or minister or priest (we were denomination-agnostic) always began by asking for a show of hands by first-time visitors. My mother always raised hers, enjoying the attention and warmth from people who hadn’t gotten to know her yet. A familiar feeling. Fleeting.

But this one time, she chose a church whose congregation happened to be in mourning because it was the preacher’s last sermon—the last one of a thirty some year career of shepherding and leading and mentoring and sharing grief.

The job of the curator is not so different from this, I think.

Everyone wore black, the sermon was about transitions, and there were so many tears. And for the first time, I didn’t want to leave. On the way home, I said to my mother, “I really liked that church; I think we should become members.”

She burst out laughing because loss was my reason for loving it. She told this story for years, any time she was trying to illustrate my particular brand of morbidity to a therapist, teacher, or, when I got older, a lover.

And here I am, all these years later, with my husband in a chapel full of people, realizing that what had been so alluring in that church all those years before, was a feeling of ease. Grief is disarming. There’s no energy for judgment or divisiveness or performativity and nobody expects anybody else to be any one way. The masks fall and postures relax, and vulnerable, complex, messy humans emerge.

I wonder if A.I.-driven surveillance technology has trouble with face recognition in a crowd full of grieving people—faces all more slack or scrunched than usual, people as themselves rather than their selves.

Stephanie’s and Kris Cohen’s introductions were ones of care, warmth, and holding—perfect prefaces to Robins’ talk, whose practice seems to be rooted in an ethos located at the intersection of preservation, compulsion, ardour, and slowness. Robins’ love for the apparently unloveable (I’m thinking about the little knitted stuffies she chagrins to collect), melts me.

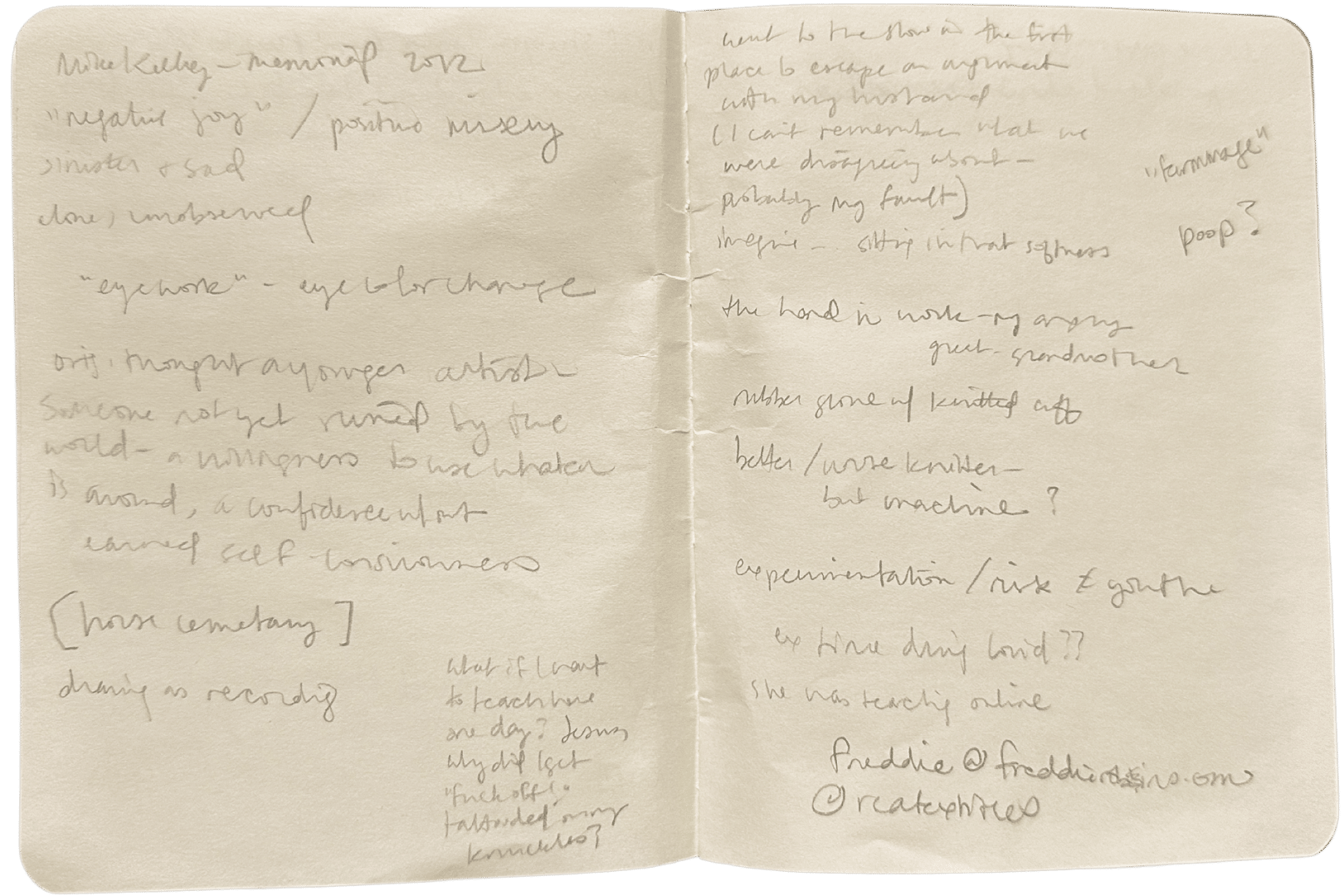

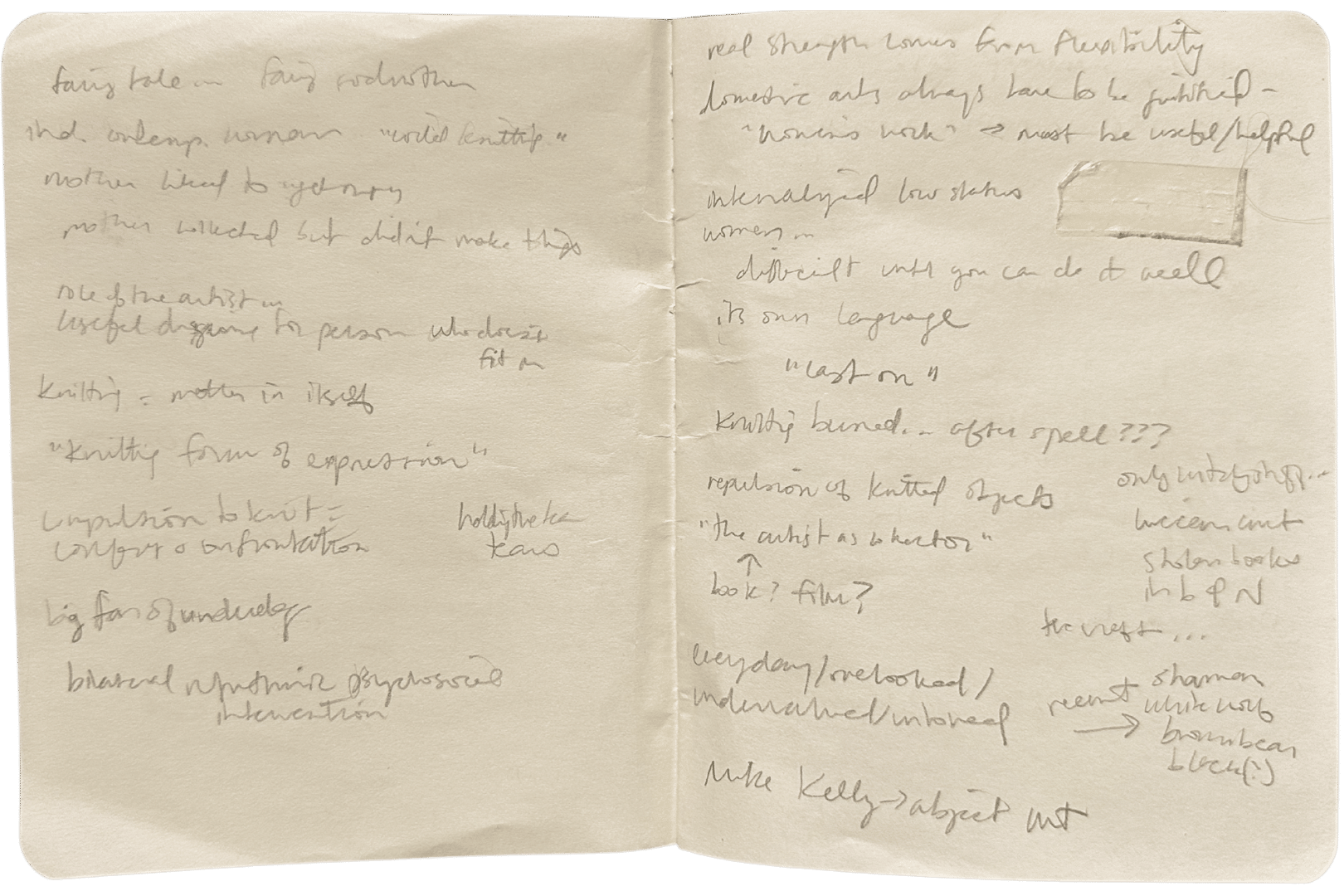

Notes I made during the talk:

| care

unapologetically soft “softness is power” interrogate intersection of art and craft human condition? textile art ≠ women’s work fairy tale … fairy introduction independent contemporary woman “coded knitting” mother collected but didn’t make things role of the artist … knitting = mother in itself “knitting form of expression” compulsion to knit = big fan of underdog bilateral rhythmic psychosocial intervention [Church Freddie Oct. 7 [Holding the tears] |

real strength comes from flexibility

domestic arts always have to be justified—”women’s work” → must be useful/helpful internalized low status “cast on” knitting burned … after spell??? [wiccan aunt the craft … (the movie)] [shaman [“eye work” eye color change] [original thought, a younger artist—someone not yet ruined by the world—a willingness to use whatever is around, a confidence with out earned self-consciousness] horse cemetery drawing as recording [What if I could teach here one day? Jesus, why did I get “Fuck Off!” tattooed on my knuckles??] |

repulsion of knitted objects

“the artist as collector” everyday/overlooked Mike Kelly → abject art “negating joy”/positive misery alone, unobserved “farmmage” poop? [Went to the show in the first place to escape an argument with my husband (I can’t remember what we were disagreeing about—probably my fault) imagine…sitting in that softness] the hand in work rubber glove with knitted cuff better/worse experimentation / risk ≠ youth ex: time during Covid |

I realize that there aren’t specific notes about the content of the talk. That’s because my note-taking practice is more about capturing shimmers, noticing moments that make me ‘go’ places, and responding. There is much available on the big wide web about Freddie Robins’ work and practice, written by much more talented arts writers than myself, and I encourage you to go read them all.

Learn more about Freddie Robins here.

[ABOUT THE ARTIST]

Freddie Robins’ practice crosses definable categories of art, craft and design. She combines these elements elegantly, and with playful wit subverts meaning and making, fusing a melting-pot of approaches to ‘craft’.

She uses knitting to explore pertinent contemporary issues of the domestic, gender and the human condition, as well as the cultural preconceptions surrounding knitting as craft. Her work aims to disrupt the notion of the medium as passive and benign. Her pieces often incorporate both humour and fear. There is also a display of almost obsessive perfectionism in the quality of each piece’s hand-made finish.

Freddie Robins’ work is in several private and public collections, including the Government Art Collection, Victoria and Albert Museum, Crafts Council, Nottingham Castle Museum, Aberdeen Art Gallery, Scotland and Kode, Bergen, Norway. She has exhibited internationally, including most recently, History in the Making: stories of materials and makers, 2000 BC – Now, Compton Verney, Warwickshire, UK; If Not Now, When? Generations of Women in Sculpture in Britain, 1960 – 2022, Hepworth Wakefield and Saatchi Gallery, London, UK; I Put a Spell on You – New Magic and Mysticism, Art Exchange, University of Essex, Colchester, UK; Creature Comforts, JGM Gallery, London, UK; Kette und Schuss, Mönchengladbach, Germany; CC binder, Puurs-Sint-Amands, Puurs, Belgium; and We are Commoners: Creative Acts of Commoning, a Craftspace national touring exhibition.

Currently Professor of Textiles at the Royal College of Art, Robins is the 2025 Stephen E. Ostrow Distinguished Visitor in the Visual Arts Program, Douglas F. Cooley Memorial Art Gallery, Reed College, Portland, OR. She lives and works in Essex, UK and London, UK.