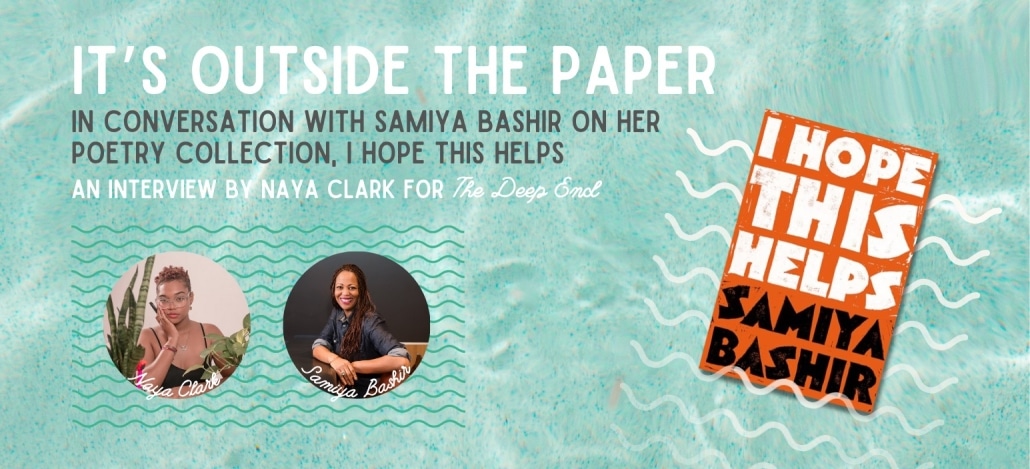

It’s Outside the Paper: In conversation with Samiya Bashir on her poetry collection, I Hope This Helps

Interview by Naya Clark

Samiya Bashir’s critically-lauded, multimodal poetry collection, I Hope This Helps (2025, NightBoat Books), begins with a quote from actress Niecy Nash-Bett’s 2024 Emmy award acceptance speech: “I want to thank me for believing in me …” This bold tribute, which echoes Snoop Dogg’s words six years prior during his Hollywood Walk of Fame ceremony speech, sets the tone for much of what’s to come in her latest poetry art collection.

Published just a few years after Field Theories, which uniquely interweaves quantum physics and Black embodiment, I Hope This Helps is the fourth poetry volume by the acclaimed poet, multimedia artist, essayist, and educator, and it promises to have at least as much impact as its predecessor.

In addition to her poetic accomplishments, Bashir is known for her opera Cook Shack (commissioned by the Opera Theatre of St. Louis as part of their inaugural New Works Collective), produced with composer Del-ShawnTaylor, and for leading Lambda Literary’s revitalization efforts as Executive Director from September 2022 through November 2023. She most recently served as the June Jordan Visiting Scholar at Columbia University in New York, and holds the 2019–2020 Joseph Brodsky Rome Prize in Literature—a distinction that resonated deeply as she became the first Black woman to receive the prestigious honor.

I Hope This Helps is an amalgamation of poetry and prose works laced with unique visuals that help expand the richness of the multimedia poetries. Experimental layouts, haunting illustrations, and suggestive sheet music punctuate the legible written words while unique typography choices—type that plays with shades of black and gray, that toggles between bold and italics, forces breaks with extreme spacing, and incorporates emoticons—make the reading of I Hope This Helps a physical experience. The addition of a QR code, which directs internet users to full bodies of work that continue off of the page, acts as a digital footnote, thus creating a truly multimodal and embodied one.

In the recurring series, M A P S :: a cartography in progress, for instance, installments are speckled throughout the collection using a black-out poetry method that transmutes existing language into new forms. The video iteration is accessible here and via the QR code at the back of the book as well.

Another piece that plays with form is HOW NOT TO STAY UNSHOT IN THE U.S.A, a two-page spread of all-caps actions listed one after the other which combine to tell the resounding and crushing story that there is no way for a person in America to feel totally protected from the possibility of being victimized by gun violence. The possibility is only amplified for folx who belong to marginalized communities and are deemed as ‘other’ by the American political and social system. ‘Offenses’ such as “BE PATIENT,” “HAVE A GUN,” “DON’T HAVE A GUN,” “BE GAY,” “GO TO CHURCH,” “BE AT HOME,” along with many haunting others, shout futility from the pages, highlighting how the looming fear of becoming a target makes for a dizzying existence for people in America—especially people of color, immigrants, women, and those within LGBTQIA+ communities.

Each of Samiya Bashir’s pieces combine to create a whole which, together, convey a richly quilted experience that helps the reader feel closer to being understood, closer to feeling part of something bigger than themselves.

In this interview, Bashir and I discuss multimodal art forms, her relationship between art and writing, and what it’s like to make art through an ‘American’ lens despite existing in its margins.

Naya Clark

I love that you start with a Niecy Nash quote. Can you go into how you decided to preface what we’ll be seeing, reading, and listening to with that? It kind of feels like permission to acknowledge yourself and could otherwise be taken as almost self-indulgent, perhaps.

Bashir

It’s the opposite. My fear is that it will be seen as self-indulgent, but the reality of why it’s there is because it’s so real, because the undercut is that I’m living in a world that not just refuses to believe in me, but insists on the opposite of me. I have a line in “LETTER FROM EXILE” [that says], “Most days America screams to anyone who’ll listen how it hates me so much / it would rather kill us all than let me live.” That’s America. That’s where I live, that’s where I’m from, that’s who I am, right? The thing is not just that this work would not exist if I didn’t somehow believe in me, but I have had to work hard and continue to—every day, all day—believe in me, because everything around me says I am not a thing to believe in. [I] trust myself to make work. It’s not a small thing, and I fight it every day. [Quoting] Niecy Nash as the opening to the book is really important to me because we can’t do this if we can’t somehow find a way to keep going. When I had the exhibition in Michigan at the beginning of this year for I Hope This Helps, one of the students in some Q&A [said], “You’re so fearless. How are you so fearless?” And I was like, “Oh, I’m terrified all the time… This is not fearlessness… I’m afraid, and I have to find a way to insist on doing it anyway.”

Clark

Do you feel a lot of this work is facing those [fears] head on?

Bashir

There’s no other way… I can face [fear] from the side, I can face from the back. I can come in through the old milk door in my grandmother’s house from the milkman days. But at some point one must stand one’s ground. June Jordan said, “We are the ones we are waiting for,” so we have to show up. We don’t actually get a choice in that.

Clark

You say you have no choice, but you make a lot of choices, especially with format. This is a whole multimedia project. And even one of the first poems, “OVERHEARD” plays with poetics. How do you decide when to toggle between various forms?

Bashir

The active agent there is me, but there’s listening, which is where I feel I really am getting to the work, in which the active agent is the poem. My decision is always to trust the poem to know what it needs. That trust helps me to identify and feel its form.

Clark

So it’s already existing. It’s a living thing beforehand?

Bashir

This is about the work, and how I can be of service to this work. What that also means is that the poem is not just a thing I made up. It’s a thing that needs to be made, and I have the privilege of being called upon to make it.

Clark

You write in “OVERHEARD,” “Once returned, I’m reminded how this whole business of writing, of sharing / is just not about me, and for good reason.” I think that’s such an omnipresent perspective of the work that you do.

Bashir

I come from a world that’s very clear that it’s not in any way about me, so to say that something is about me is kind of a revolutionary act. I want to be clear about when I engage [with] that, and when it’s right. I don’t believe that the art I make is about me. I think it’s about us. But I also don’t necessarily believe in a me that is supercilious to us.

Clark

You take a more conversational approach with “OVERHEARD.” I appreciate how accessible your work is—so much of it feels like how we [may] think and how we talk. You’re not trying to be overly flowery, and you’re not trying to put yourself in the confines of structure and language. One of my favorite parts in “OVERHEARD” is where you say “AND WHAT AM I TO BE—RAW OUT HERE? Entrails all exposed? / Skinless?! Nah, B! Nawwwww.” How did you make that decision?

Bashir

Everything is written, revised, rethought, made clear.

Clark

I mean, there’s emojis.

Bashir

It was what I meant. ¯\_(ツ)_/¯

One poem was published in an anthology before the book came out, but the anthology publishers [suggested] I replace those [text emoticons] with the actual emojis and I was like, “No, no.” I personally am a little obsessed with the language of captions…[when] you’re watching something—I’m fascinated by the way they reframe what’s happening… It’s important to be clear about how we think about things, how we represent things to each other, and then how we also experience it. If you’re writing, you have to filter your experience into these letterbox spaces… That is a wrestling with language.

I am in love with language. I am also the greatest critic of the English language. It’s not my jam. It’s my native tongue, yes. The most fluent language I speak, and probably will ever speak in my life. And I also think it’s probably one of the least poetic languages on the planet. American English is a miracle every day. But what I’m doing here is not flowery because I’m actually trying to communicate something. I’m not trying to talk over or around you.

One of my great pet peeves is the way poetry is taught as a puzzle you’ll never be smart enough to solve… [I Hope This Helps] is not trying to trick you, because why would I do that? That’s beside the point. How could it help if it’s all a trick, [or] it’s all a joke? I Hope This Helps—the earnesty of the title is real. If you were at a reading, I would be looking you in the eye. I’m not speaking to the middle distance. I’m really trying to talk to you.

Clark

It’s not all words. There’s line breaks, parentheses, brackets, [and] em dashes. You play with font size and boldness, color [and] white space. What is your process in deciding pause? Or a moment for the reader to take a pause with a space or a symbol.

Bashir

This work—it’s very embodied, right? I think of poetry as primarily an oral art…right through the ear, through the body. [It’s] something that we’ve carried in our bodies long before writing. Language is not just words. We talk about body language. That’s a real thing.

When we talk about spoken language, I think that the breath [and how it’s scored] is critical. I really do agree with the idea that what you see on the page…that’s not the poem. That’s just a delivery system to get the poem from my body to your body… It’s a musical score sheet. If you’ve ever read music, the idea is: I can take this beautiful piece of music, put it on paper, and you can pick it up with your instrument, follow that on the paper, and play it. That’s what I’m doing on the page with the poem.

There are times when a semicolon is going to do something and a colon is going to do something, and a stanza break is going to do something else, and a line break is going to do something else. Or a long deep breath, which I might have to put in brackets to tell you: No, I really mean take a long, deep breath.

I tell my students, [to] read poems out loud. Don’t just sit there and read them silently. There’s sound happening here, and sound does something to our bodies physically. If you go to the movies and you see how they’re scored…the music has been set up to do this to our bodies in advance. That’s what poetry has the opportunity to do as well if you’re scoring it right. [Sometimes] the language that I’m working with in video poetry is about light and the dust in the light and the color and the movement of the body. Sometimes, if it’s in performance, it’s again in the body.

I think of I Hope This Helps, the installation piece that’s focused on the Standards, as a performance. One where my body steps out so your body can step in, the performance as you move through these 20 Standards hanging in space. It’s listening [and asking], “What does this poem need?” This poem is not just about words. This poem is about something much bigger. Poetry does something to us. There’s a reason. It’s perhaps the oldest art form that exists…aside from and alongside cave paintings. We’ve done this since we’ve had language…

Clark

Have you always been experimenting with these forms or is it something that you evolved into?

Bashir

I guess the answer is yes. I mean, I think in terms of writing and making…I’ve always been experimenting. But what [I experiment] with grows as I grow. Being able to play with language, play with grammar, play on the page, versus dealing with performance—all of these things are different areas, and so many of them have opened up in my poetry.

Clark

I’m just always thinking about how you have to kind of learn the rules to be able to break them. You have to learn those rules of grammar to know how to play with the rules of grammar. Same with music, for instance.

Bashir

Yes. You can’t be a dancer if you don’t have any relationship to gravity, right? But this is dance, and you have to understand how space and force and measure and gravity work. It’s the same thing I used to teach [in] dual workshops with my dance colleagues when I was at Reed College. We would do composition workshops, because poetry composition and dance—they’re two different things. But also, are they? How do we think about what we mean when we’re using this language, and what we’re doing with it, and how they might be in concert [or] in conversation, and help each other think about [them] in different ways?

Clark

Speaking of movement and structure, this is a full collection, all the pieces living with each other. How do you work with something that’s meant to stand alone versus something that’s meant to be in a collection? Do you make every piece separately, [or] are you thinking about it as a family?

Bashir

Everything can stand alone, but that doesn’t mean it’s not part of a conversation. I think about my work really in terms of conversation… When I think about sending work out for publication, magazines or journals, it’s like I’ve got this kid [who] now gets to go out and play, gets to go to school, gets to meet other friends and be in conversation with what’s happening in the world. That conversation is everything. It’s what it’s there for… It’s not about me. I might have made this thing, but it actually exists outside of me and beyond me, and I have to let it go and live its own life… You get to kind of see what that is, which for me is always a surprise. Now I get to sit down and listen to the work say, “This is who you are. Let me help you be who you are.”

Clark

I’m also thinking of your lengthier poems like the MAPS series. I know that there’s no right or wrong way to perceive poetry or collections, but what was your process in making that a series? Was it one long thing and then you broke it up? Or was there a theme that you saw and decided they all belong together?

Bashir

Actually, it predates my last book, but I knew it didn’t belong in that book… It’s a found poem project pulled through a novel called Maps by Somali literary legend [Nuruddin] Farah. That novel is breathtaking. It’s part of his Blood in the Sun trilogy and the whole series is breathtaking. All of the language in [my Maps series] is pulled from that novel, and it creates a whole different story. There’s definitely a tension between a mother figure and a lover there, and tension between how one maps one’s own coming of age, one’s own becoming, one’s own existence in a world that is actually not here for our wellness [or] our existence. It’s always a cartography in progress… It’s a project that I don’t know will ever be finished. I still have not completed pulling language from that novel. But this is the piece as it is now, as it needs to be in an unfinished state. I may continue to add to it…over time, but I think what it needed to be was presented and clarified—as this is a process of becoming, not a process of having become.

Clark

Another thing that I noticed is that you are not afraid to say, “I don’t know.”

Bashir

It’s probably the truest answer I could give to most things.

Clark

There are also places where you have more blanket life statements. The things you feel you know, how do you know [when] to put it in a poem?

Bashir

I get by with a little help from my friends. We show each other the work and help each other find paths toward understanding and at some point I have to trust and believe, not just that I’ve learned a few things—but that there might be some value to that. I also have to trust [that] what I know through deep experience and observation and understanding and thought and work, is also what I have to offer… So if I keep it a secret then, well, that just feels kind of selfish and not really helpful.

Clark

I also want to know about incorporating photography, typography, [and] sheet music. What is the logistical process of speaking with your editor or publisher, and getting on the same page?

Bashir

I mean, one thing I want to say full stop is that I am grateful to Nightboat Books, Stephen Motika, the publisher; Kazim Ali, the founder; and the whole team there. Stephen and Kazim have really believed in me and my work… This project is important because it’s about a collaborative building… That is also one of the guiding principles of this book… I don’t actually want you to read all the texts. I want you to see how the text and the images work together. Then you can go and actually see the video and hear the music, hear it through the voices and the bodies of the singers, and see how all those things work together.

The video poem, negro being:: freakish beauty—same thing. It’s just a transliteration. You have to go see the whole piece yourself. “DARK MATTERS” is the same thing. It’s on Spotify. Go hear it. But you can see what we’re doing when the musical notes mash up with the language notes, which then come together to build a whole new language, which is a whole new piece.

That’s what I’m working to recreate for you in book form… This is beyond book form. This is just the ink-on-tree version of this. [If] you want to hear, see the whole thing, experience the whole thing, it’s outside of the paper. If I’m delivering it right, soon it might be in your body too.

Clark

I feel a lot of writers or artists may feel restricted by what they do and the form that they feel or have been taught that they need to take. From your perspective, how might a writer or an artist know that their work may work best as multimedia?

Bashir

One of the things that I think we’re culturally stuck in right now is this fear of failure, fear of being wrong. [That] if you say the wrong thing, [you’re] gonna be canceled and it’s over, and [you’re] gonna be mocked, and [your career/life is] done. But we have to be willing to try something. Many of the things that I do with this work, I didn’t know how to do before. But I had to do it, so I had to learn. (Fortunately, learning might be one of my favorite things!) So I figure out how to do something, because that’s what the poem needs. And I probably had to try many different things before I got it.

In my last book, I have another series called “Coronography”, which is a double sonnet crown. It’s really busting through the sonnet form to do the work that those poems needed. So I have to really move through the form and understand what it does, then I can know how I can use that form to do what the work needs it to do. That doesn’t mean that I need to blindly follow a rule. I need to understand the rules and know why they are there and what they exist to do. Then comes what I need to do with them.

Clark

You mentioned a large part [of I Hope this Helps] is collaboration and relies on having a good publisher, good people that you can ask, “How do I do this?” or, “How can we work together to do this?” What’s an example of something you didn’t know how to do that you needed to turn to and collaborate with someone else with?

Bashir

The piece called “Here’s the Thing:” which only exists because I had been commissioned to write a libretto with a composer for a choral piece structured for a chorus and orchestra. It was my first time working with a 250 person chorus and a bazillion person orchestra. [It was] my first time working with this composer too, and as [I was] working to get this libretto together, what became clear for me and this process…is that I had to write it as a poem [first], and that’s what set the libretto free. Then I could write the libretto.

Clark

With the constant doom and the feelings that everyone was experiencing [since Covid], how did you decide to write about this?

Bashir

One of my great heartbreaks—probably of my life—is how, in 2020, we had this terrible opportunity globally, as a people—as a humanity—to do something different. In two weeks, air pollution vanished. We watched the earth heal in a month. But then everybody was like, “Nah…”

Well…when do we start actually caring for each other? That’s [what] part of this book is. We have to figure out how to care for each other. For ourselves. Especially now, when it can so easily feel–at every turn–as if all just might be lost.

An early poem in the book, “Per Aspera,” ends with: ”I can’t say how we heal / I wish / I could / I would / I’ll try:” And I remember when that poem came through, I immediately knew that was how the book opened. It may have been the first day I actually saw the book itself finding its form.

Clark

I mean, you said the title is earnest, but objectively, what do you want people to get out of it?

Bashir

Well, I think, first, I hope people can feel seen and heard and known and not alone. The piece that spreads across two pages, “HOW NOT TO STAY UNSHOT IN THE U.S.A” is also one of the Standards in the installation. When the show was up at Michigan State University in January, I [was] really worried, because [they] had [their] own mass shooting in 2023, and that piece is a kind of a chronicle of recent mass shootings across the United States. I didn’t want to trigger kids. Not just kids, but the whole community there. But what happened was the opposite. These students came up to me in tears, but because they were so grateful for that piece. “It’s like nobody talks about it,” one young student said, who had been there. This sense of erasure, or back-to-normaling that we do well, that too is what we do with COVID, what we do with trauma and abuse and oppression and harm and this work sees that. Shows that. Loves us through it.

This is real, this poetry says, what we’re going through right now. And you’re not going through this by yourself. I see you, I hear you. I’m right the fuck here with you.

You can learn more about Samiya Bashir at her website, samiyabashir.com, and order I HOPE THIS HELPS at NightBoat Books. You can also order the book directly from your favorite local bookshop or attribute the sale to them via Bookshop.org.

Visit Samiya’s calendar for updates on happenings, including her August multimedia poetries workshop at The Fine Arts Work Center in Provincetown, Mass.

Learn more about the author of this interview, Naya Clark, at her website, nayaclark.com

Ryan-Ashley (Anderson) Maloney is the editor for our interviews and critical essays.

* This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents are producs of the author's imagination. Any resemblance to real events or persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental.